Marriage Certificate Luigi and Loretta/Loretta

The Plan[edit]

The Dawes Report stressed in its introduction that "the guarantees we propose are economic and not political in nature".[10] The resulting Dawes Plan covered payment amounts and timing, sources of revenue, loans to Germany, currency stabilization and ending the Ruhr occupation:

- Reparations payments began at one billion Reichsmarks the first year, increasing annually to two and a half billion after five years. No total sum was set.[9] The terms included a prosperity index, based on which Germany would have to pay more under favourable economic circumstances.[11]

- The sources for reparation payments included taxes on customs duties, alcohol, tobacco and sugar, and revenue from railroads and the budget.[10] As a guarantee for payments, the German National Railway was converted into a corporation under creditor-state supervision. An interest-bearing mortgage on German industry for 5 billion Reichsmarks also served as a guarantee.[12]

- The Reichsbank was reorganized under the supervision of the creditor states. It had seven representatives from the creditor states and seven Germans on its board [13] and was independent of the central government.[4]

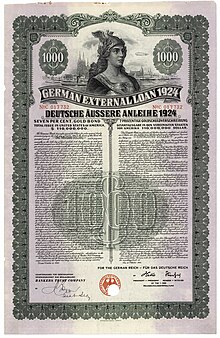

- Germany was loaned 800 million Reichsmarks to be the base capital of the central bank and to ensure the Reichsmark’s stability.[12] About half of the sum was raised through Wall Street bond issues in the United States.[6]

- The Allied Reparations Commission was replaced by a Transfer Committee which was to take the value of the Reichsmark into consideration when making payment transfers.[12] Payments were not to be made if they endangered the gold that backed the Reichsmark. Repayment of commercial debts took priority over reparations payments in order to maintain Germany's creditworthiness.[14]

- Foreign troops were to be withdrawn from the Ruhr.

Reichstag approval[edit]

The debate over the Dawes Plan in the Reichstag affected the formation of a new government following the May 1924 Reichstag election. The Communist Party of Germany (KPD) saw the Dawes Plan as economic imperialism, and the Nazi Party objected altogether to paying reparations.[6] Many on the political right objected to it because of the limits it placed on German sovereignty (control of the Reichsbank and the national railroad). The right-wing nationalist German National People's Party (DNVP) had campaigned against the Dawes Plan and gained 24 additional seats, making it the second strongest party in the Reichstag after the Social Democrats. The party's refusal to change its stance on the Dawes Plan resulted in Chancellor Wilhelm Marx of the Centre Party remaining in office presiding over a centrist minority cabinet.[15] Since the clause in the Dawes Plan regarding the German National Railway required a change in the Weimar Constitution and therefore a two-thirds majority in the Reichstag to pass, it was necessary for some DNVP members to vote for acceptance. A number of influential industrial and agricultural interest groups urged the DNVP to accept the Plan, with the result that it passed on 29 August 1924 with the help of 48 DNVP votes.[16] The Dawes Plan formally went into effect on 1 September 1924.

Results[edit]

The influx of foreign credit led to the upswing in the German economy that underpinned the "Golden Twenties" of 1924–1929. Overall economic production increased 50% in five years,[9] unemployment fell sharply and Germany's 34% share of world trade was higher than it had been in 1913, the last full year before the outbreak of World War I.[6] By the start of the world economic crisis in 1929, Germany had received 29 billion Reichsmarks in loans. In spite of the stronger economy, Germany was unable to achieve the trade surpluses necessary to finance reparations. It met almost all of its payments under the Dawes plan[17] but could do so only on the basis of its large foreign debt.[18] Most loans were short term, which meant that they could be quickly called in if the creditor nation experienced an economic downturn.[14] Germany found itself heavily reliant on foreign capital.

The occupation of the Ruhr ended on 25 August 1925.

Germany considered the Dawes Plan to be a temporary measure and expected a revised solution in the future.[17] In 1928 German Foreign Minister Gustav Stresemann, the former chancellor, called for a final plan to be established, and the Young Plan was enacted in 1929.[19]

Charles Dawes received the Nobel Peace Prize of 1925 “for his crucial role in bringing about the Dawes Plan”, specifically for the way it reduced the state of tension between France and Germany resulting from Germany's missed reparations payments and France's occupation of the Ruhr. British Foreign Minister Sir Austen Chamberlain shared the prize with Dawes, although his award was for the Locarno Treaties, which dealt with post-war territorial settlements.[8]

Feme murders

The Feme (German pronunciation: [ˈfeːmə]) murders (German: Fememorde) were a series of murders in the Weimar Republic between 1919 and 1923 carried out by German far-right groups against individuals they believed had committed treason against them by betraying their secrets. They were considered a distinct category from politically motivated assassinations of public officials. By the time the Feme murders ended, they had claimed almost 400 victims. In spite of a number of investigations, few of the perpetrators were ever identified or prosecuted.

Definition[edit]

Feme (from Middle Low German veime, meaning punishment), in the usage of right-wing extremist underground movements, referred to an act of vigilante justice – the killing of "traitors" who, as members of their own groups or as outsiders, knew about weapons caches or other internal secrets and had reported them to the authorities or threatened to do so. One of the groups most involved in the murders, the Organisation Consul, an ultra-nationalist, anti-Semitic and anti-communist secret society founded in 1920, stated in their statutes that "Traitors fall to the Feme".[1]

The term is sometimes also used to refer to the political assassination of democratic politicians such as former Reich Minister of Finance Matthias Erzberger (1921), Karl Gareis of the Bavarian parliament (1921) and Foreign Minister Walther Rathenau (1922), as well as the failed assassination of Philipp Scheidemann (1922) by members of the Organisation Consul.[2] According to political scientist Hans-Helmuth Knütter, these assassinations, as well as political assassinations from the left, should be distinguished from Feme murders.[3] A Reichstag committee in 1926 similarly distinguished Feme murders from other political murders by limiting the use of the term to murders perpetrated by members of a group against those who betrayed secrets. This included similar acts by far left groups.

Number of victims[edit]

Nearly all of the Feme murders occurred during the turbulent early years of the Weimar Republic. A peak was reached in 1923 when hyperinflation, Allied occupation of the Ruhr, Adolf Hitler's Beer Hall Putsch, and separatist efforts shook Germany. By 1924 a total of nearly 400 of their political opponents[4][5] had fallen victim to right-wing radical and National Socialist assassinations by the Organisation Consul, the Viking League, the Black Reichswehr, the Sturmabteilung Roßbach, the Bavarian Citizens' Defense and their successor organizations. Within the Black Reichswehr, First Lieutenant Paul Schulz commanded a special unit that killed those who were seen guilty of betraying the country by leaking military secrets.[6]

Reactions[edit]

The first to attempt to study the phenomenon systematically and for all of Germany was the statistician Emil Julius Gumbel, who in 1922 presented the paper Four Years of Political Murder (later updated under the title From Feme Murder to the Reich Chancellery). Gumbel was subjected to serious threats because of the study.

While the Weimar judiciary rigorously prosecuted leftists involved in the German Revolution of 1918–1919 and in the political activities of the Bavarian Soviet Republic, police and judicial investigations of the Feme crimes were slow, and the murderers, insofar as they were identified, got off with light sentences or even acquittals. Mid-level military officers such as Paul Schulz of the Black Reichswehr were eventually convicted and imprisoned before an amnesty for the Feme murders was declared in 1930, but Germans who exposed the killings were tried and convicted for insulting the military establishment for their role in doing so, even when their allegations against the military were true.[7]

The obvious deficiencies in law enforcement were matters of concern for several parliaments during the Weimar period. In 1920 the state parliament of Bavaria set up its own investigative committee to look into the Feme murder of Reichswehr soldier Hans Dobner. In 1924 the state parliament in Prussia set up a "Political Murders" investigative committee, and two years later instituted a second. In November 1925 the journal Die Weltbühne published an unattributed article by Carl Mertens, a German officer and pacifist, about the Feme murders of more than twenty members of right-wing groups.[8] In January 1926, at the request of the Social Democratic Party (SPD), an investigative committee of the Reichstag, under the name "Feme Organizations and Feme Murders", was set up to clarify the crimes and their political environment in parties, the Reichswehr and the judiciary.[9] The project was hindered from the beginning by the right-wing majority in the parliament, the Bavarian judicial authorities' refusal to cooperate,[10] and not least by the indecisiveness of the SPD itself.[11]

A year or so ago now I signed up with a service that has access to records to build family trees. In the interim I've learned quite a bit more history than I knew before that. The service sent me a link to this

Comments

Post a Comment